What do Body Pump classes, Coca Cola and the iPhone have in common?

Their soaring success is in part due to their intangible qualities – parts you can’t feel or touch.

The future of the intangible economy

While they are harder to measure, intangible assets are a critical part of our economy today. Investment share of intangibles has increased by 29% since 1998, while Bill Gates described the intangible economy as “one of the biggest trends in the global economy that isn’t getting enough attention”.

So what are they, how do we measure them, and what do they mean for the future?

Jonathan Haskel is the co-author of the groundbreaking book: ‘Capitalism Without Capital: The Rise of the Intangible Economy’.

He is a member of the Monetary Policy Committee at The Bank of England, and a Professor of Economics at Imperial College Business School.

Q: Where did your interest in economics start?

A: I studied Economics at the University of Bristol, and I had the great fortune of having a series of extremely stimulating teachers. In fact, two of the professors who taught me actually went on to win Nobel prizes! I became fascinated with economics, because I thought it was about some of the most interesting problems in the world.

Q: When did you first think: maybe there is another type of capital beyond the tangible things like machines or buildings?

A: A standard economic seminar is all about manufacturing. And part of the reason for that is because the data is more easily available, and it’s easier to measure. If you want to measure the output of a ball-bearing or steel factory, the physical units are simply the number of ball-bearings or tons of steel.

But at the same time, when I graduated from university, none of my friends went into the ball-bearings industry. Nor did they go into the steel industry. They were doing these more intangible activities – being accountants or consultants, designers or musicians or programmers. Their jobs were creative, imaginative and intensive in knowledge capital.

So to make sense of what they were doing, it struck me that it would be much more interesting to go outside of manufacturing. And that's why I started researching that area of the economy, because I thought it would be helpful in understanding how the economy has changed.

What is an asset?

An asset is something which a company builds, which gives it an enduring flow of services

A plane is an asset because it provides you with with an enduring flow of services – the ability to fly from A to B for 20-25 years

Planes are made up of both tangible and intangible assets

Some examples of tangible assets....

Intangible assets are assets that you can't touch or feel

What is an asset?

An asset is something which a company builds, which gives it an enduring flow of services

A plane is an asset because it provides you with an enduring flow of services - the ability to fly from A to B for 20-25 years

Some examples of tangible assets...

Some examples of intangible assets...

“

Anybody who's had a piece of Apple or Microsoft equipment would know that the product is much more than the equipment. It’s the buzz around it; the look, the feel. These intangible notions are very important in thinking about the core attractiveness of many products.

Q: What value do we gain by naming economic trends and activity?

A: I think naming is quite helpful. What we're doing here is not just an economics exercise; we're also looking at the reason for company success and failure. So there’s a crossover between what we do in the accountancy profession and the management science profession. Setting firm classifications and methods for measurement means that individuals across different sectors can talk to each other.

This is particularly important when talking about more slippery concepts, like digitalization. People talk a lot about the ‘digital economy’ – but what do we actually mean by this?

Subdividing the digital economy into the bits that are tangible (e.g. computers) and the bits that are intangible (e.g. software) is a good way to make sense of it. Then, if you were in the consultancy business, you could start asking firms: ‘How much hardware are you buying? How much software are you buying?’ So I think naming makes things more focused.

How can we measure intangible assets?

01

Identify how much the firm has spent on intangible assets (e.g. software, databases, artistic originals and design). This includes both purchases, and “in-house” investment assets (which can be calculated through labour force surveys.)

02

Calculate how much of that spending will last for more than a year.

03

Multiply the amount spent by the fraction that is long lasting. This is the nominal investment.

04

Adjust nominal investment for inflation and quality change e.g. compare £500 spent software today with £500 spent five years ago). This is the 'real' investment.

“

If a firm were to announce that it's very committed to having beautiful products and fantastic design, we (the statisticians and economists) don’t set any store by that. Talk is cheap; any firm can say all of that.

Q: What do we gain by measuring intangible assets?

A: I think what it means is that we get a much better understanding of modern economies.

In the 1930s, like we've seen during Covid – parts of the economy were doing incredibly badly, so it was really important to figure out what was going on. Statisticians would go out and measure what they could – the steel industry and the car industry, for example – and then could go to policy makers, treasury secretaries, the Chancellor of the Exchequer and say, “look, steel's going up! Cars are going down.”

But the trouble with that is that the steel goes into the cars, so you’re not allowed to count the steel industry and the car industry, because you're just double counting. What you've got to count instead, is the value added: the cars minus the steel, because you've already counted it. And that's what GDP does – it’s essentially a way of taking out all of those inputs which you've already counted as you go all the way up the production chain.

Increasingly, these inputs are intangible inputs. If I’m working for the British Museum, and I count all the people that visit the museum and all the software, I'm double counting, because part of the reason why people is because they're logged onto the software.

If we want to keep track of all the different stages of production, we, as a society, need to actually measure these different stages, and when they change and be more intangible, we need to measure those stages too.

The four 'S's of intangibles

The four 'S's of intangibles

01 Scale

Physical assets can only be used in one place at one time. An iPhone typically only serves one user.

However, intangible assets (e.g. apps) can often be used over and over, in multiple places at the same time, at relatively low cost.

For example, an iPhone can only be being used in one car at one time, but a mapping app on that iPhone could be being used in multiple cars, at different times, on roads all over the world.

02 Sunk cost

Tangible assets, like phones, buildings or land, are not-specific to the business that owns them. This means that they can be useful to many types of businesses.

Intangible assets, like apps, patents or brands, are more likely to be tailored to the specific needs of a company. This means that they’re likely more useful to the company that created it, compared to anyone else.

Sticking with the iPhone example, you can sell an old handset, but you can't sell your subscription to the Spotify app on that handset.

03 Spillover

Many intangible investments have unusually high spillovers – the tendency for others to benefit from what were meant to be private investments.

When it comes to tangible things, however, competitors can’t steal them (without the breaking the law in doing so!)

For example, today there are many competitors in the takeaway space thanks to food delivery software being relatively easy to copy.

04 Synergies

Many intangible investments have unusually high spillovers – the tendency for others to benefit from what were meant to be private investments.

When it comes to tangible things, however, competitors can’t steal them (without the breaking the law in doing so!)

Q: What do you think it is about investing in intangible assets that gives firms that competitive edge?

A: It gives firms something which other firms can't potentially do. Let’s take the example of Apple. You might think: “Surely somebody else can make a phone like an iPhone?” Well, Nokia tried that, and they couldn't do it. Microsoft has tried over and over again in various different programs, but they also found it difficult. So we think it’s the combination of these intangible assets, which makes successful companies’ distinctive features particularly hard to imitate.

When Steve Jobs tragically passed away, what was interesting from a company point of view is that Apple didn't fall to pieces overnight. In other words, the reputation of the company – the talent, the skills and so forth – was not embodied in him personally, rather the company overall.

That shows that there’s something very interesting about how companies are able to make the skills and talents of individuals add up to more than the sum of their parts (the synergies). And that's going to be the secret to their enduring success.

“

If people can gather synergies, assemble them in a firm, and get an end product out, the rewards are likely to be very profound. But for someone to manage all the parts, we think that this requires more than just management. It requires leadership.

The evidence for intangibles

Research from McKinsey & Company used sector-level data and a survey of 860 executives to measure and analyse company investment in intangibles. Read the full report here

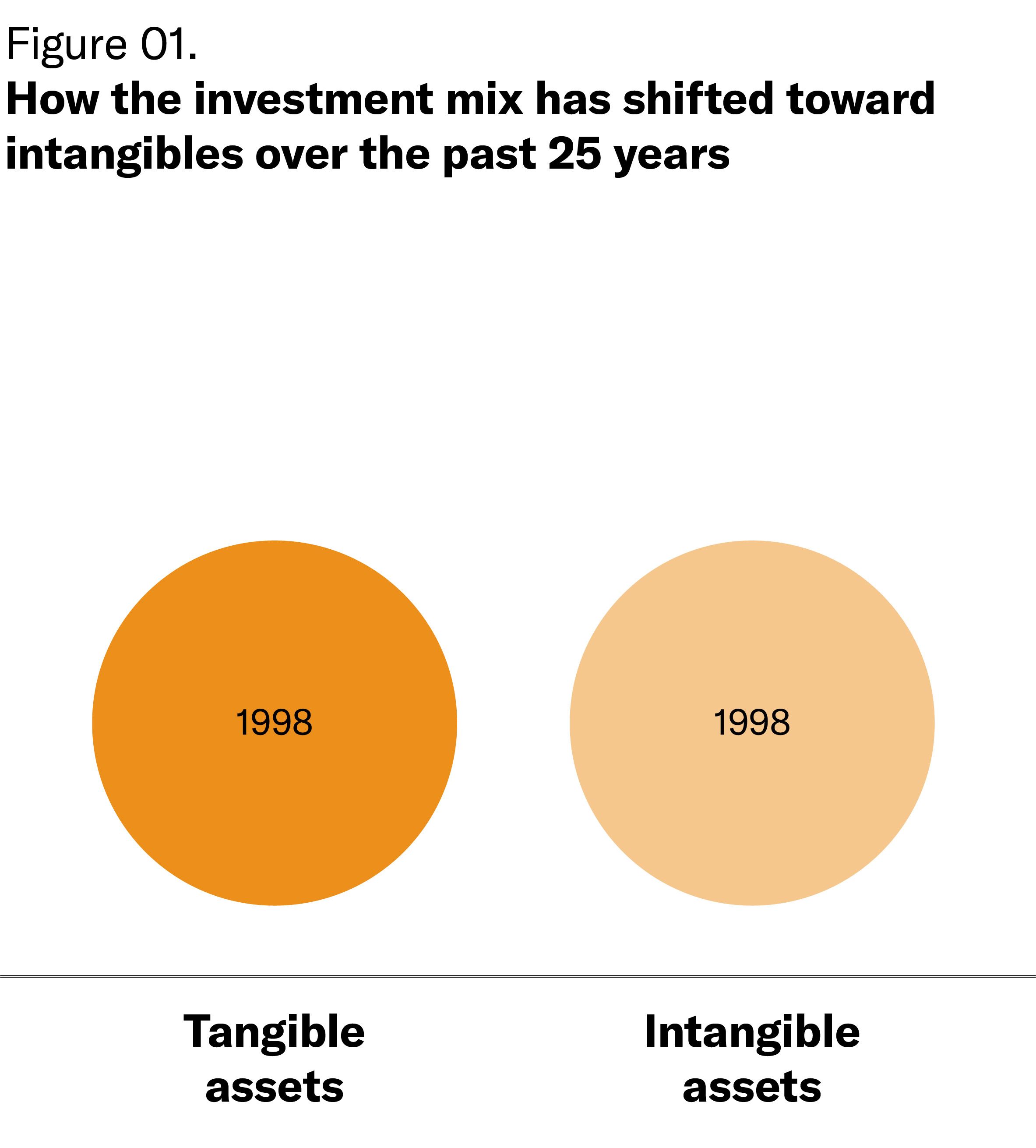

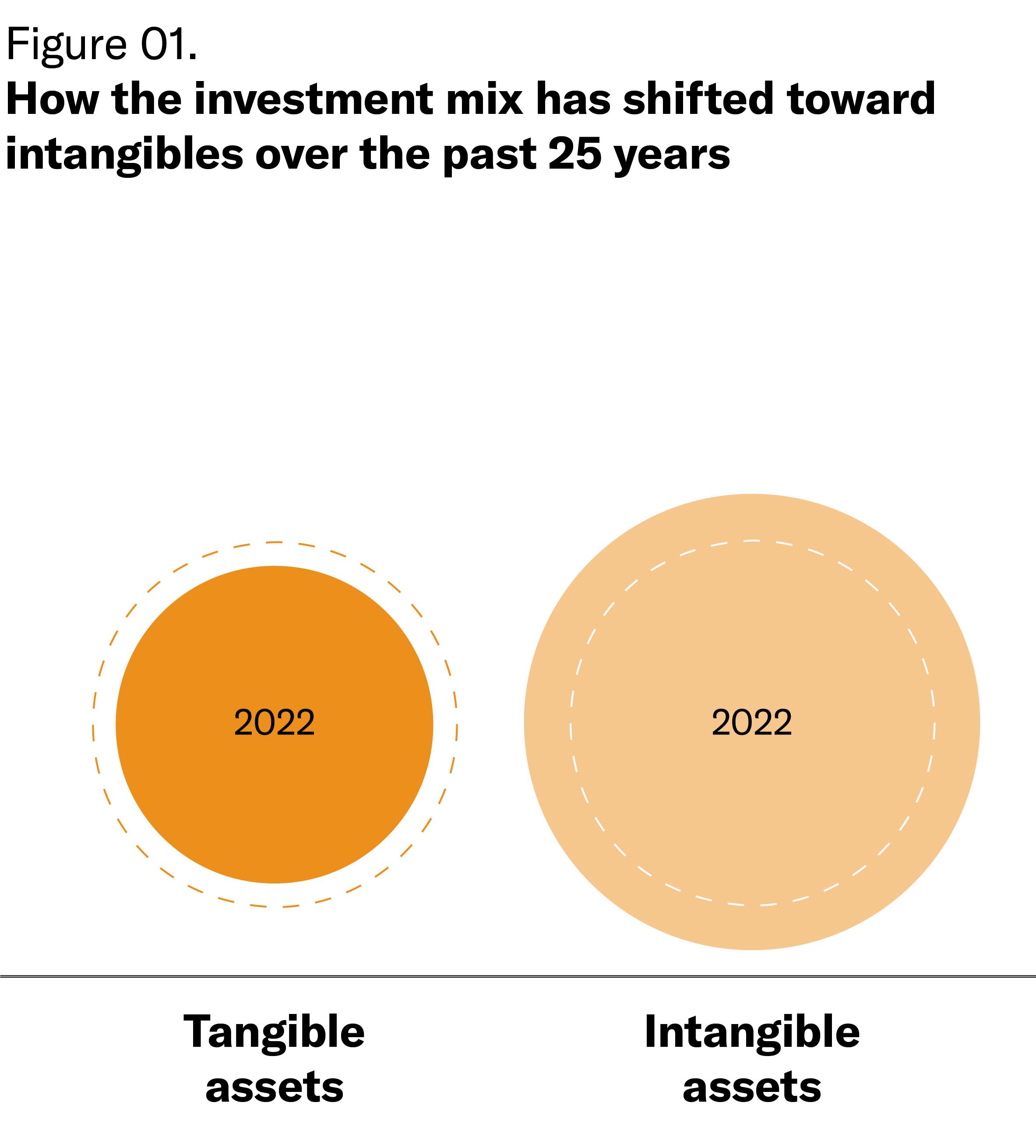

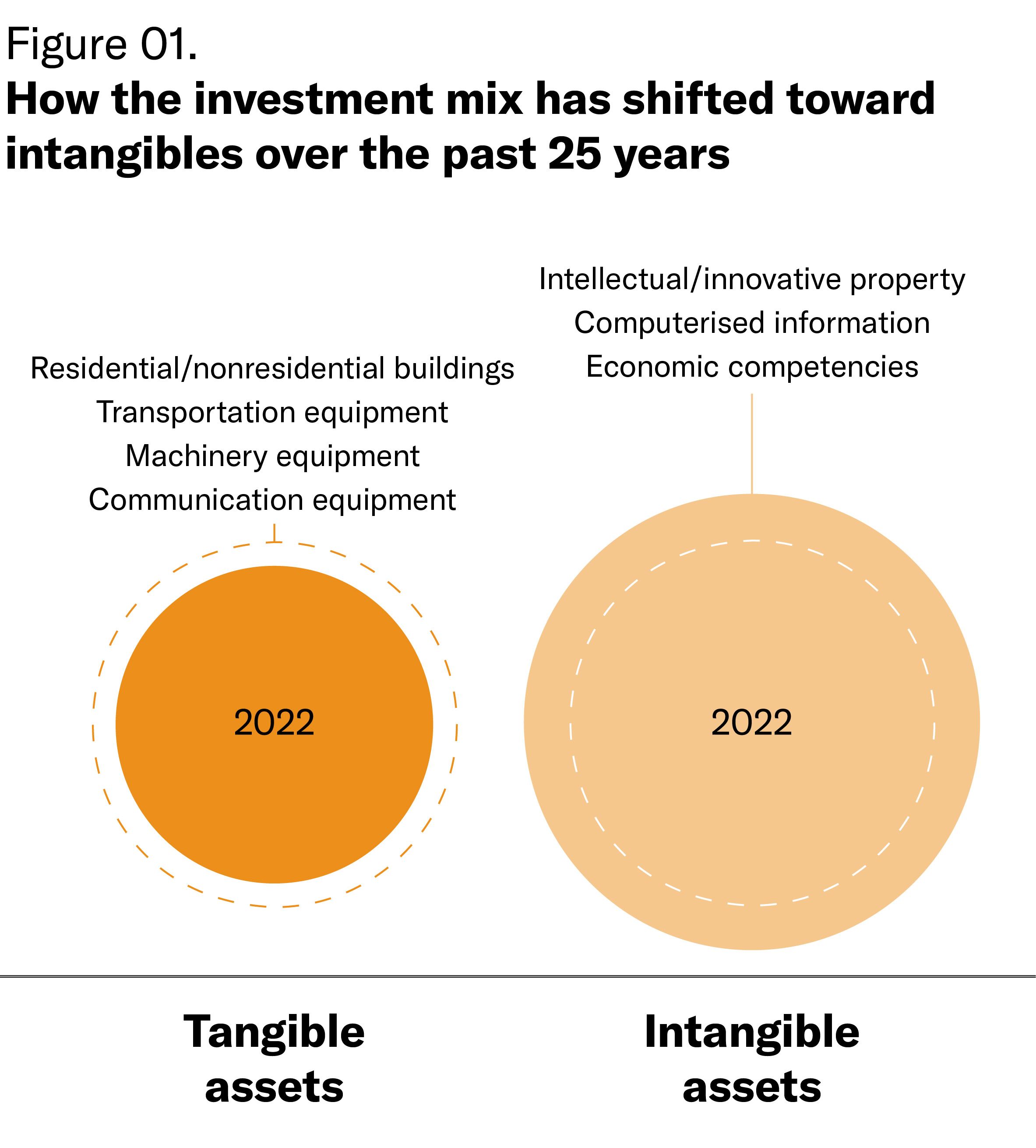

Figure 01.

How the investment mix has shifted toward intangibles over the past 25 years

Research from McKinsey & Company finds a marked shift towards intangibles in US and 10 European countries since 1998.

The investment share of intangibles has increased by 29%

Key intangible sectors include intellectual / innovative property, computerised information and economic competencies

The investment share of tangibles has decreased by 13%

Key tangible investments are buildings, transportation, machinery and communication equipment.

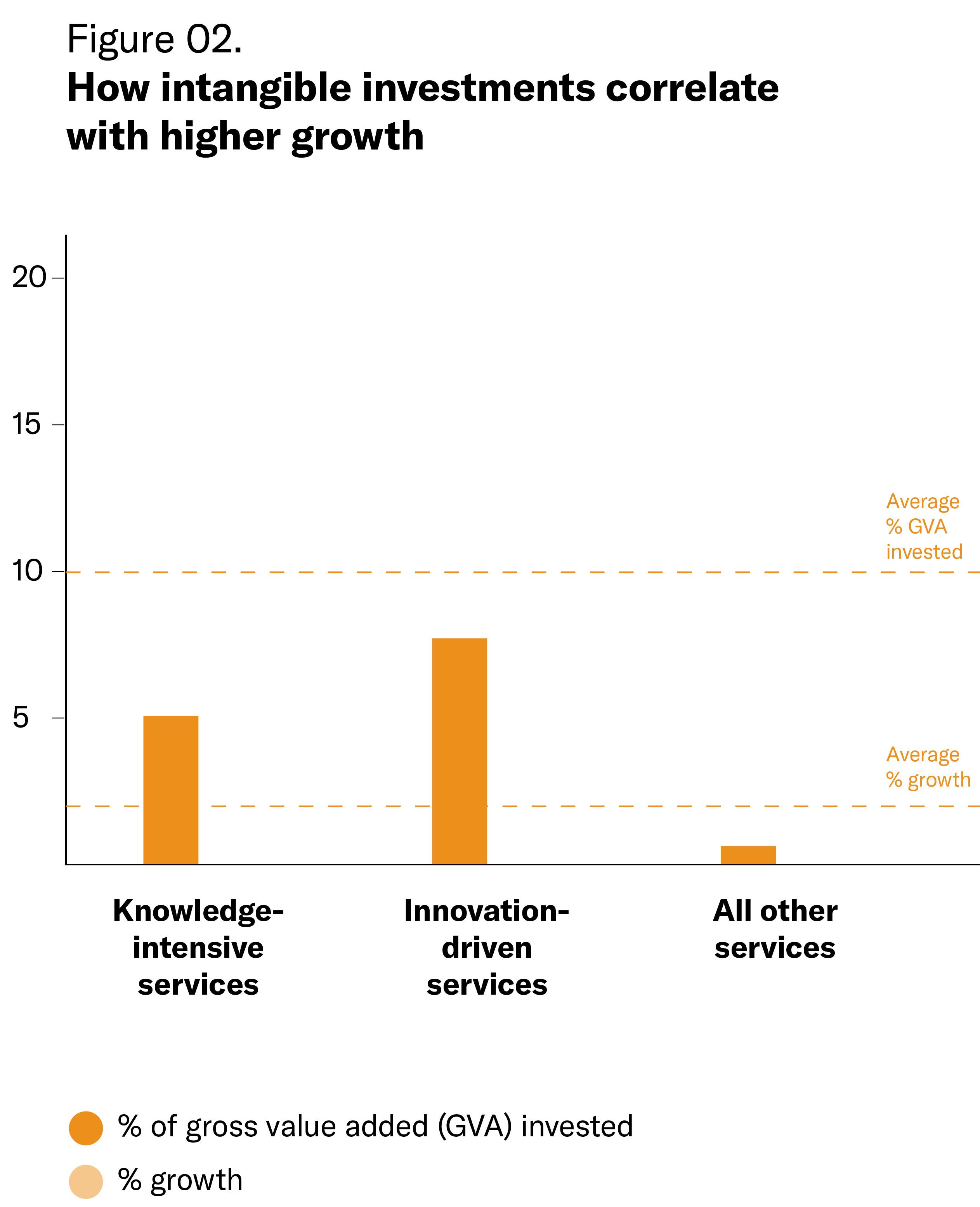

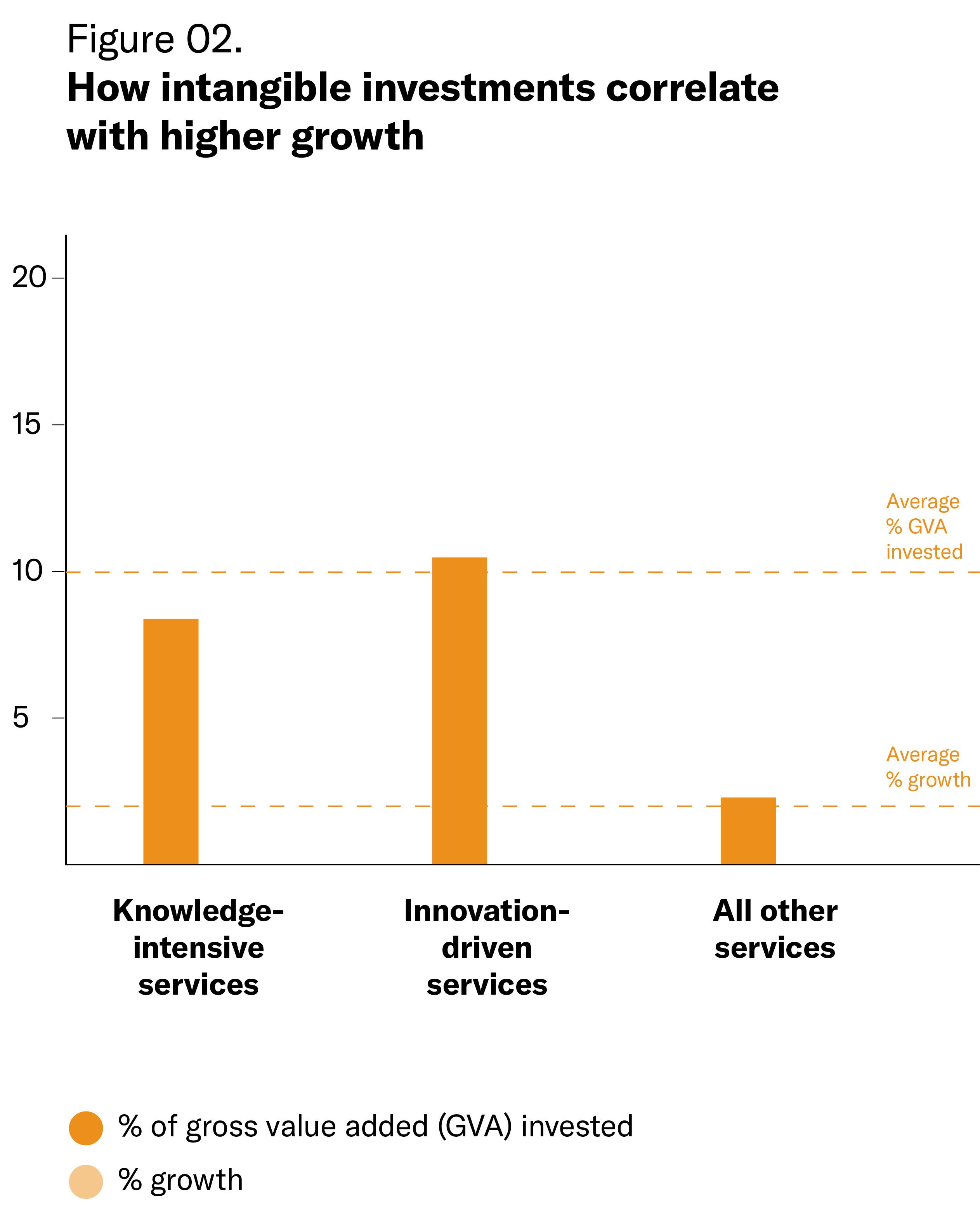

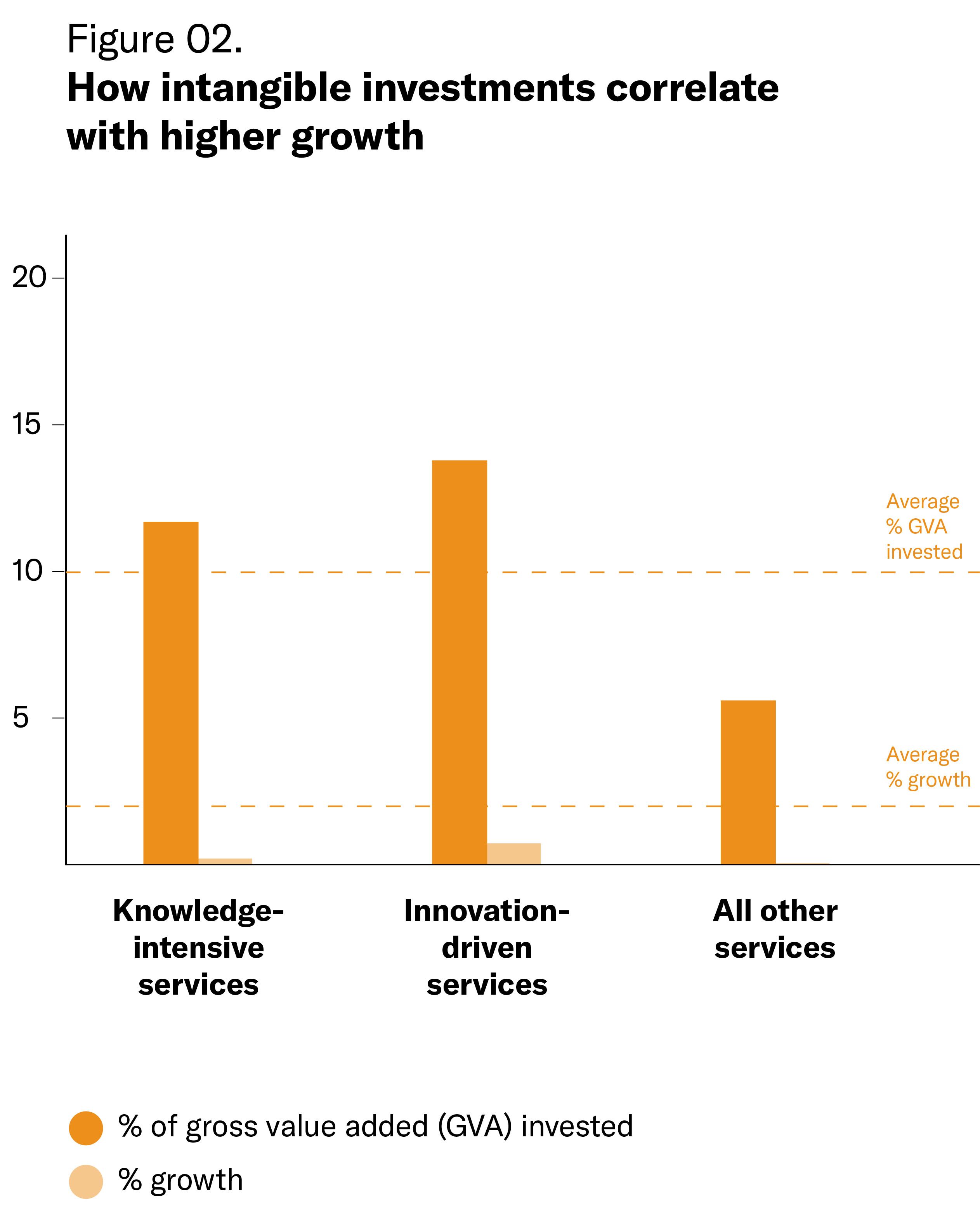

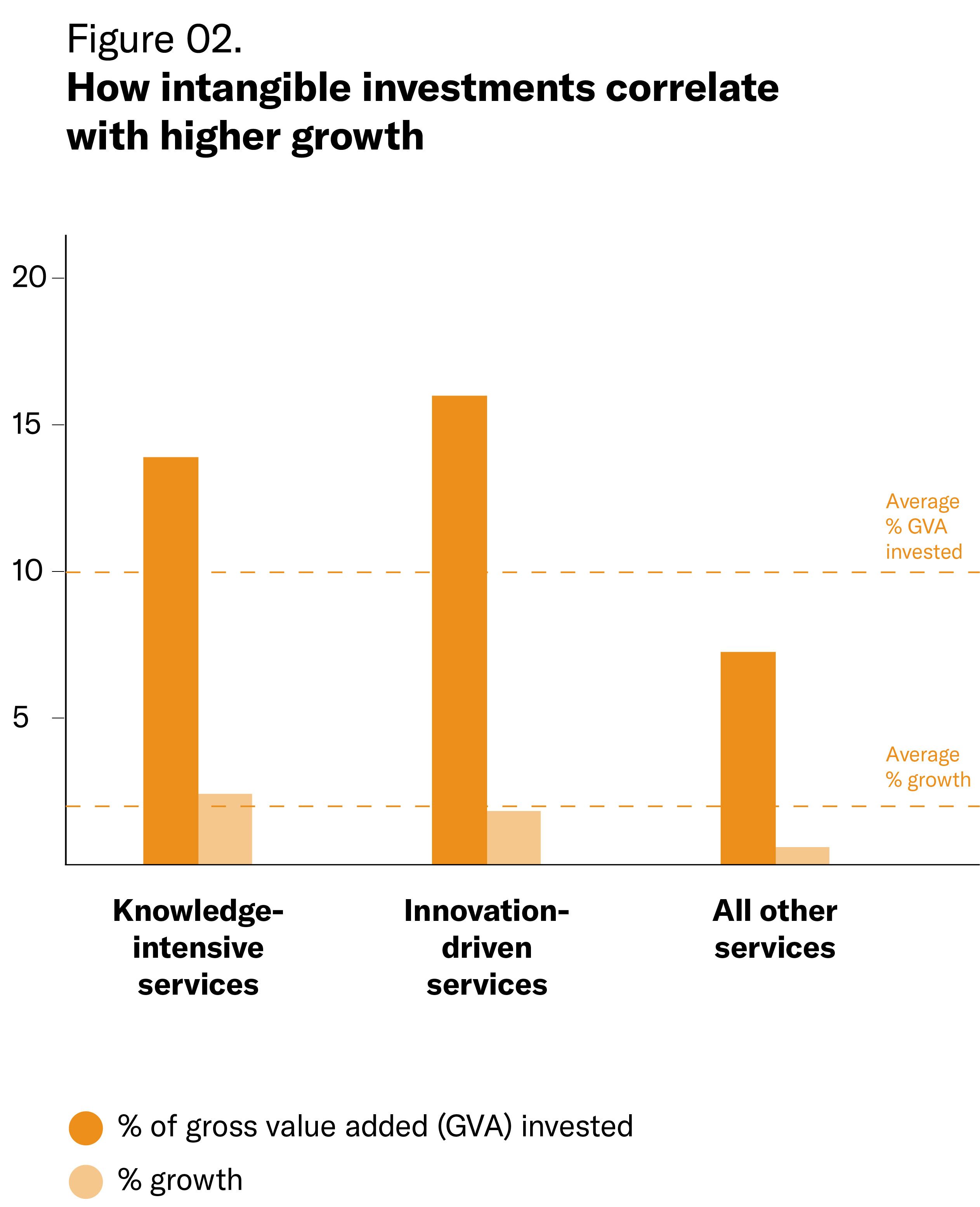

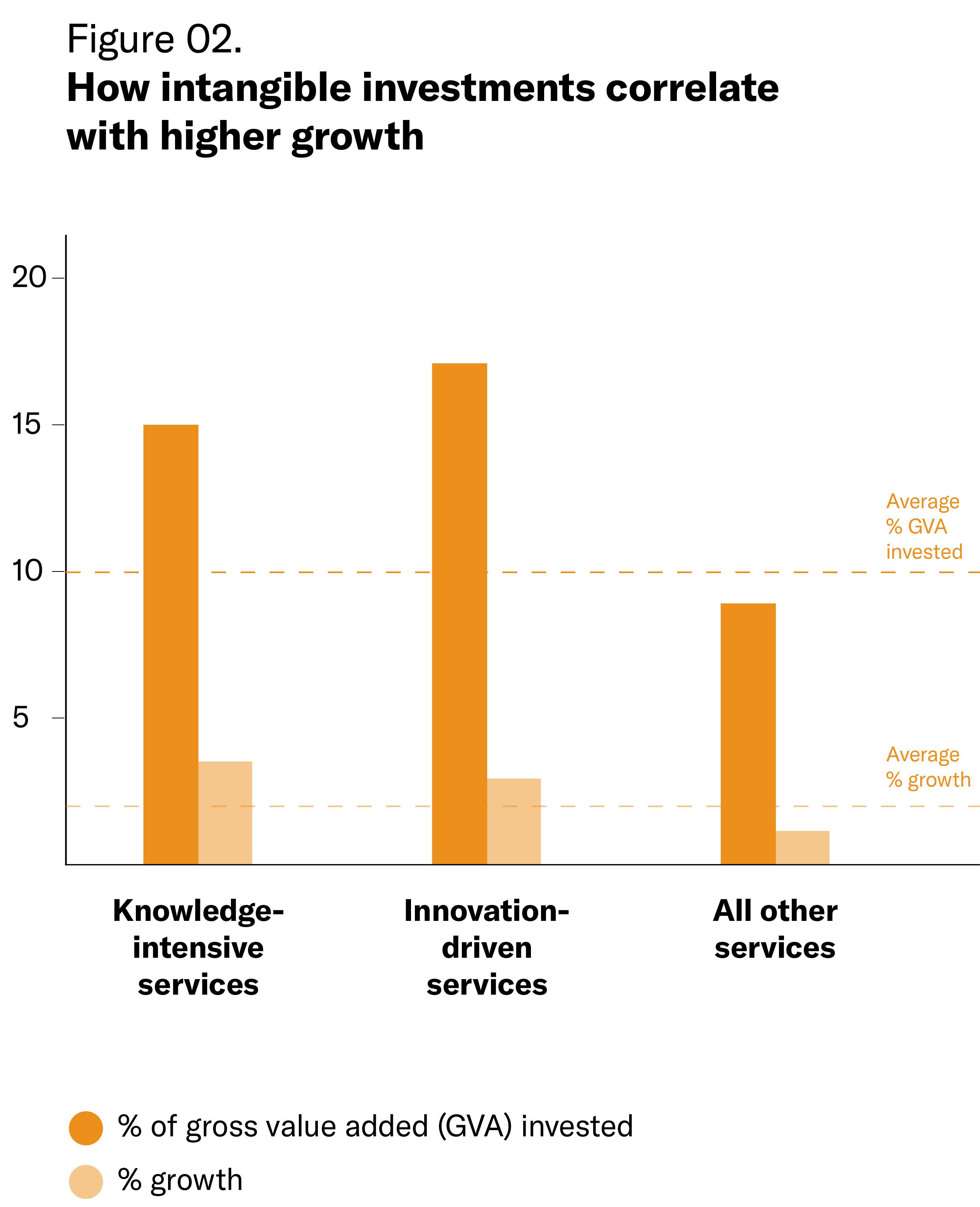

Figure 02.

How intangible investments correlate with higher growth

This McKinsey research also measures percentage gross value added (GVA) invested in intangibles, against annual percentage growth to gauge how companies investing in intangibles are benefitting.

The results are promising. Average GVA invested is 10-12%. Sectors that have invested more than this have 28% higher growth than other sectors.

Knowledge-intensive services (such as science and engineering) saw an above-average return, with 3% growth after 15% GVA invested in intangibles.

Similarly, innovation-driven services (such as IT and technology) invested 17.4% GVA and saw a 2.9% growth rate.

Most other sectors invested less than 10% of their GVA and achieved below-average rates of growth.

Q: In ‘Capitalism without Capital’, you wrote that companies rich in intangible assets require leadership, rather than just management. Why is this the case?

A: If people can gather synergies, assemble them in a firm, and get an end product out, the rewards are likely to be very profound. But for someone to manage all the parts, we think that this requires more than just management. It requires leadership, because these individual talents need to have faith in the person who's trying to coordinate all of these activities, otherwise they’ll go elsewhere.

So we make the case that leadership is more important than repetitive management – shuffling pieces of paper around and doing some of the more routine things – which is common in a lot of management today.

Q: Another important word in ‘Capitalism without Capital’ is trust. Why is trust so important to intangible economies?

A: I think it has an increasingly important role. When we were a hunter-gatherer society living in tribes, they hadn’t invented the internet and planes, so people didn't travel very far. This meant that there was very little commercial interaction outside your immediate family, and tribe and trust was incredibly important. But all of that has gone away now, in our globalised business.

If I buy an iPhone, I've never met the person who put it together, or the person who shipped it over. But nonetheless, I trust Apple to deliver me a nice iPhone. Companies need to have that burden of trust in a way that communities had that trust before.

The early history of retailing, for example, is essentially a trust business. If you were going to buy medicine for your child, and you go to a shop that’s got some large jars, you've got no idea what it's selling. But once companies like Boots came along, they acquired trust. So trust becomes an important part of modern day transactions.

This relates back to the idea of ‘synergies’. If a manager or leader is going to pull this stuff together, they need to be trusted even further. So we think a return of this sort of trust is going to be part of the future for these intangible style economies.

How intangibles impact economies

A company starts off small, with some intangible assets

It grows over time, investing more in intangible assets (e.g. brand or user experience)

Companies who possess intangible assets can scale up, gain synergies and become incredibly successful

But there is a counter force - companies rich in intangible assets are easier to copy, resulting in more competitors

However, the spillover’s force for equality is insufficient against the forces from synergies and scale - resulting in inequality between firms

Q: You wrote ‘Capitalism without Capital’ in 2017 – pre-pandemic and pre-Brexit. How have your thoughts evolved since then?

A: In the book, we noted that since the financial crisis, investment in intangibles (which before the financial crisis has been very fast), had slowed right down. At the time we thought this was a symptom of the very slow recovery from the crash. But as the years have gone by, another five years since we wrote the book, those investment rates have remained very slow. So our next book, ‘Restarting the Future: How to Fix the Intangible Economy’ is really about the consequences of that. The second issue is Covid.

Interestingly, the only class of investment which has gone up during the pandemic is intangible investment. The airlines aren't buying planes anymore, and companies aren't buying buildings. But firms are investing in software, more digitization, and more R and D.

That surely is related to the kind of structural shifts that we're going to see in the economy towards more working from home, more remote shopping, all those kinds of things. So we think that the post Covid economy, if anything, is going to be more intangible intensive rather than less.

Q: How can governments invest in intangibles, without exacerbating inequality?

A: At the end of ‘Capitalism Without Capital’, we laid out a puzzle: despite spillovers, which are a force for equalisation, the distance between firms appears to be going up. In other words, the spillover’s force for equality has been insufficient for the inequality forces from synergies and scale.

The new book takes this up in the following way: suppose you are a young firm, and you see an opportunity – possibly you think of some spillovers, and you think you might be able to knock one of the big firms off their perch. The thing you're going to need is funding. However it’s very difficult for firms to secure funding for intangible assets, like a better piece of software or a better movie script.

So we think that we really need some reforms in the capital market, so that the banking system becomes much more nimble and able to fund these new firms. Because if we can do that, these competitive kinds of effects would erode away, which would allow firms to catch up.

Q: What do you want the legacy of your work to be?

A: If my work helps anybody in the general public to have a think about the world and see the world better; or improve policies and fix things that are broken, that would be a lovely legacy.

The benefits that intangible assets can bring to a firm are exponential, yet exploiting these benefits is no easy task. It’s undoubtably harder to measure intangible assets than things that we can tangibly feel and touch; and assembling intangibles within a firm is an equally challenging task. But the firms that are doing so, and are deploying them effectively, are thriving.

We need to get better at quantifying intangible assets, finding ways for organisations to keep track of this area of investment; and developing the right combination of strategy, creativity and trust to bring their value to life. As we look towards an increasingly unpredictable future, the adaptability of intangibles will be paramount for business success.

Glossary

Asset - A resource with economic value that an individual, corporation, or country owns, which gives it an enduring flow of services.

Tangible asset - An asset that you can touch and feel, such as a building or a plane.

Intangible asset - An asset that you can’t touch or feel, such as software or design.

GDP (Gross Domestic Product) - a monetary measure of the market value of all the goods and services produced in a specific time period in a specific country.

Synergy - when the interaction of two elements produces a greater effect than the sum of the individual parts.

Scalability - a property of a system that enables it to sustain or better its performance when demand increases.

Sunk cost - money that has been spent and cannot be recovered.

Spillover - an economic event that occurs in one context and leads to an economic event in a seemingly unrelated context.